What is Plagiarism?

Plagiarism is theft.

It is using someone else’s material without giving him or her credit. Whether it’s in an essay, part of a class presentation, on a poster you hang up at school, in a video you share online – trying to pass someone else’s ideas off as your own is stealing. It doesn’t matter if your friend said you could use his ideas … you still have to quote him. And it doesn’t matter if you didn’t know you were using someone else’s ideas. It’s still your fault for poor research practices.

Consequences of plagiarism…not even famous people can escape

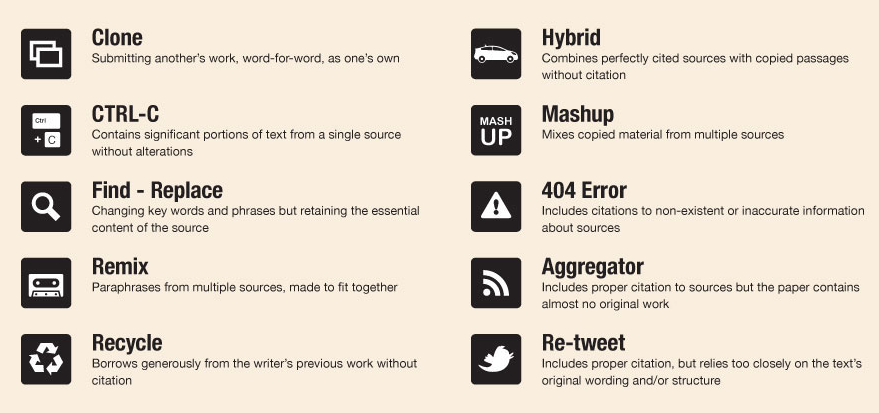

Turnitin, an online service for plagiarism prevention and proofreading, lists the following types of plagiarism, from most severe (Clone) to least severe (Re-tweet):

For the image above, if I hadn’t referenced Turnitin or included the download information and URL, I would have been plagiarizing. Even if I had renamed the types of plagiarism and used my own clever icons but didn’t reference Turnitin, it would still be plagiarism because the basic idea came from there.

A famous instance of “Find – Replace” plagiarism occurred a few years ago, when noted historian Stephen Ambrose was found to have borrowed key phrases, syntax, and ideas from other historians. For example, in his book The Wild Blue (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), Ambrose wrote, without quotation marks or referencing,

“No amount of practice could have prepared the pilot and the crew for what they encountered – B-24s, glittering like mica, were popping up out of the clouds over here, over there, everywhere.” (164)

Six years earlier, another historian, Thomas Childers, had written in his book The Wings of Morning (New York: Perseus Books, 1995),

“No amount of practice could have prepared them for what they encountered. B-24s, glittering like mica, were popping up out of the clouds all over the sky.” (83)

Coincidence?

While Ambrose’s reputation was long solidified as a popular historian, his legacy was tarnished and he died a year later, as further cases of plagiarism surfaced. While you may not die as a result of plagiarism, the point is that even famous people get caught stealing words and ideas. It’s a serious matter.

Why and when do I have to cite?

Proper citation is essential for academic writing integrity. Citing sources serves three important purposes:

It acknowledges that others have contributed valuable information to a given subject, and it also shows that you have the skills and ability to work with a variety of ideas.

Section 8 of the First Article of the United States Constitution grants Congress the power “to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries”. In other words, the United States government has the power to make and enforce patent and copyright laws.

The copyright law of the United States is embodied in Title 17 of the United States Code. For specific details, see Copyright Clarity by Renee Hobbs, or Copyright Basics, which is made available by the U.S. Copyright Office.

Assume that everything is copyrighted except United States government publications. However, even references to US government publications should be cited properly. This includes unpublished works, which have the same copyright protection as published works. Copyright law also governs the making of photocopies of copyrighted material (which is why you can’t copy an entire book).

Properly citing sources legitimately adds your own work to the body of knowledge out there in the world. It’s like being part of a huge conversation. This means that someone may one day cite YOU as a source.

As a rule of thumb, if an idea originates with another person or your original thought is a response to another’s idea, you must use a proper citation to credit the people who influenced your thinking, whether the idea is published or not.

Where citation gets a little fuzzy is the gray area of “common knowledge,” things like historical events, factoids that “everyone knows,” or observations about people, for example. But even learned scholars differ on what can be called “common knowledge.” Generally, if you find the same piece of information in multiple, varied sources (three or more is a good rule), or a wide range of people know it, then it is common.

Below are some essential things to keep in mind as you are researching and writing your coursework. This is obviously not an exhaustive manual on academic writing, but it covers some important recommended standards.

Keep full references of everything you read

Keep them from the beginning and update them as you go. Not only does this help you keep track of what you’ve read, but it can easily be turned into your formal bibliography/works cited list.

Read Widely

The more you read, the better idea you will have about what you are studying, and the more you will be able to formulate your own thoughts rather than rely on one or two sources to say what you need to say.

Keep your notes and writing separate

Put all your notes in one document or file folder, and your actual writing in another. This will help prevent you from copying directly from a source and pasting into your writing. When you do consult your notes for information, look at them side by side with your writing so you are working from them, not just using them.

Save each draft separately

Every time you do major editing or revising, use the “Save As” function to save the draft as a new document. Use a numbering system like “Dissertation draft_v.01” This helps you keep track of when and where you made changes.

Contextualize long quotations

Even when you put long quotes in your notes, be thinking about how they will fit into your arguments and how you will use them to reach your conclusions. It may be helpful to write interpretive notes alongside a quoted passage, so you are already working with the material before you even start writing your actual text. Include what you think the passage is about, how the author uses it, how you will use it, and where it fits into your overall research plan.

Check and double-check your references

As soon as you incorporate a quotation or paraphrase into your thesis, go over the reference to make sure you have written the correct wording, denoted exactly where the quote begins and ends, and marked the appropriate page number(s).

Speak for yourself

Your sources are meant to substantiate what you say, but not to say everything for you. Yours should be the primary voice in the text. It’s okay to use someone else’s ideas as a springboard for your own, but you should always make it clear that you did this.

Ask for help

When in doubt about how you have used source material, speak to a professor or librarian. It is better to be safe than sorry when it comes to plagiarism.

Try to paraphrase and summarize whenever possible. Paraphrasing means to rewrite something in your own words. Obviously, you would still have to reference the source, because the ideas aren’t yours. But the syntax (arrangement of words), emphasis, and especially interpretation, should be original.

Example: Original passage:

“It has to be said that many leaders, not least Christian leaders, even when they do not succumb to this degree of malevolence, fill the positions around them with less competent people, thinking that they thereby preserve their own image or authority. They don’t of course; they simply become masters of incompetent administrations. On the long haul, their own reputations are diminished. But jealousy is such a blind sin that such obvious realities cannot be admitted.” D. A. Carson, “August 26,” For the Love of God Vol. 1 (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 1998), n.p.

“It has to be said: many leaders, not least Christian leaders, even when they do not succumb to malevolence, fill positions around them with less competent people, thinking they thereby preserve their image and authority. They don’t—they simply become masters of incompetent administrations. In the long run, their own reputations are diminished. However, jealousy is such a blind sin that such obvious realities cannot be admitted.”

Why it’s bad: a few words were changed or deleted (“this degree,” “the,” etc.) and a couple punctuation marks were changed. But the passage was copied almost verbatim.

“Carson (1998) says we must recognize that many leaders, even Christian ones, may not give in to the kind of malicious behavior that Saul exhibited towards David. But they still surround themselves with less competent people, hoping to keep up appearances and maintain their positions of authority. Of course they don’t, because they just become leaders of incompetent administrations. The end result is that their own reputations are tarnished, not just by association, but also because they end up approving decisions that are foolish or even wrong. Sadly, such people cannot acknowledge even obvious truths like these, because jealousy is such a blind sin.”

Why it’s still bad: larger chunks of text were rewritten or reorganized, a little summary of Carson’s earlier material was included, and a few original thoughts were added. There is even a reference. But the ideas and conceptual structure remain the same, and there is next to no original interpretation.

“In the devotional for August 26, Carson discusses how Saul’s selfish jealousy of David had tragic consequences, not the least of which was the destruction of Saul’s own reputation. We naturally want to make ourselves look good, and when we are threatened by others’ successes, we think our own self-images are thereby weakened. So we surround ourselves with people who appear less smart or capable or beautiful. The pride that results from this only serves to make us the ugly ones. But “jealousy is such a blinding sin” (“August 26”) that we do not recognize it in ourselves, leading us, like Saul, to do angry, hateful, and even violent acts against the people we perceive as hurting our reputations.”

Why it’s good: it references where the discussion originated, as well as the direct quotation (using the entry title because there were no page numbers). It reinterprets and re-contextualizes the source material. Though it still reaches the same conclusion (jealousy blinds us), it has a different application for people in general, not just leaders.

How to Format Citations

Most of the programs at Missio prefer, but don’t require, Chicago style. The MA in Counseling (MAC) program requires APA format. The ThM and DMin require Turabian (which is essentially Chicago … see below). When in doubt, check with your professor. We highly recommend that you keep a copy of the latest edition of the appropriate style guide on hand while writing your papers, or use the listed online guides. You can use Citation Machine or the built-in citation option in later versions of Microsoft Word for all styles except SBL.

Below is a quick guide for the different citation styles you may encounter at Missio. Also check out our Citations Handbook, a comprehensive manual for understanding and constructing proper citations. It includes numerous examples of the most common types of sources, using the Turabian, SBL, and APA citation styles.

Citation example: Hanneken, T. (2014). The watchers in rewritten scripture: The use of the book of the watchers in Jubilees. In A. Harkins, K. Bautch, and J. Endres (Eds.), The fallen angels traditions: Second temple developments and reception history (pp. 25-68). Washington, DC: Catholic Biblical Association of America.

– Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 6th ed.

– APA Style Guide FAQs

– Citing eBooks in APA style

– Video tutorials from MU

Citation example: Hanneken, Todd R. “The Watchers in Rewritten Scripture: The Use of the Book of the Watchers in Jubilees.” In The Fallen Angels Traditions: Second Temple Developments and Reception History, ed. Angela K. Harkins, Kelley C. Bautch, and John C. Endres, 25-68. Washington, DC: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 2014.

– The Chicago Manual of Style, 16th ed.

– Chicago Manual of Style Online Quick Guide

– Video tutorials from MU

Citation example: Hanneken, Todd R. “The watchers in rewritten scripture: The use of the book of the watchers in Jubilees.” The Fallen Angels Traditions: Second Temple Developments and Reception History. Washington, DC: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 2014. 25-68. Print.

– MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers, 6th ed.

– The MLA Style Center

– Everything You Need to Know About MLA Citations (EBSCO eBook)

– MLA video tutorials from MU

Citation example: The Turabian manual is actually a version of Chicago tailored for student papers as opposed to published works; the example citation is identical to the one for Chicago.

– A manual for writers of research papers, theses, and dissertations, 8th ed.

– Turabian quick guide

– eTurabian.com

Citation example: Hanneken, Todd R. “The Watchers in Rewritten Scripture: The Use of the Book of the Watchers in Jubilees.” Pages 25-68 in The Fallen Angels Traditions: Second Temple Developments and Reception History. Edited by Angela K. Harkins, Kelley C. Bautch, and John C. Endres. Washington, D.C.: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 2014.

– The SBL Handbook of Style, 2nd ed.

– SBL’s Student Supplement to the SBL Citation Style Guide

– Pitts Theology Library SBL Citation Builder

Further reading on plagiarism, writing, citing, and other matters academic

- Missio LIB 101 – For Missio faculty & students: information on using the Missio library, but includes sections on citations, bibliographies, and academic research and writing

-

Drew, Sue & Rosie Bingham – The Guide to Learning and Study Skills: for Higher Education and at Work

- IUB Writing Guides – The formatting’s a little odd, but they cover some very useful topics

- Neville, Colin – The Complete Guide to Referencing and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Pecorari, Diane – Academic writing and plagiarism : a linguistic analysis – An excellent look at how and why students accidentally commit plagiarism

- www.plagiarism.org – A good overview site that covers paraphrasing, citations, bibliographies, footnotes, and more

- Purdue Online Writing Lab – Lots of helpful stuff related to academic writing, including resources on plagiarism and citations

- turnitin.com – Tips on improving your writing and avoiding plagiarism