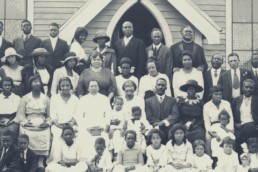

February and March are important months of remembrance. In February we honor African Americans and in March we honor women who have played important roles in history. I would like to combine these two remembrances and introduce you to a great African American woman and a six-foot tall fire-breathing abolitionist, women’s rights activist and Christian evangelist: Isabella Baumfree (c.1797 – 1883).

Born into slavery around 1797 (the birth dates of most slaves are uncertain), Isabella was one of the ten (perhaps as many as twelve) children born to James and Elizabeth Baumfree both of whom had been kidnapped by slave traders and sold to the Hardenbergh family of New York. In 1806, nine-year-old Isabella was sold at an auction with a flock of sheep for $100 to a sadistic master who beat her without mercy. She was bought and sold several times before ending up in the household of John Dumont.

Around 1815, Isabella made the mistake of falling in love with a slave named Robert from a neighboring farm. Robert’s owner however, forbade their relationship. Robert was savagely beaten when he was caught visiting Isabella, and she never saw him again. She eventually married an older slave named Thomas with whom she had five surviving children.

Late in 1826, Isabella made one of the most painful decisions of her life—she escaped to freedom with her infant daughter, Sophia, but had to leave her older children behind. She found her way to the Quaker family of Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen, who took her and her baby in. Isaac then purchased the run-away slave and her daughter for $20. Although she was safe, her other children were not. She learned that her five-year old son Peter had been sold to an owner in Alabama. With the help of the Van Wagenens, she took the issue to court and in 1828, after months of legal proceedings, she got her son back. Isabella became the first black women to go to court against a white man and win the case. That same year (1828) the state of New York mandated that all slaves be emancipated and her family was reunited.

It was during her time with the Van Wagenens that Isabella became a devout Christian. She gave herself the name Sojourner Truth in 1843 after she became convinced that God had called her to “testify to the hope that was in her.” She moved to New York City, worked as a domestic and became a street-corner preacher. Although illiterate she nevertheless acquired a wide knowledge of the Bible and emerged as one of the leading advocates for women’s suffrage.

In the years that followed Sojourner Truth combined evangelism with advocacy for the rights of former slaves and women. Some years later, when speaking in Boston, Massachusetts, she recounted how her mother told her to pray to God that she might have good masters. She told how her various masters beat her for not understanding English and how she would question God why he made such evil masters. She admitted to the audience that she had once hated white people, but she said after she met Jesus, she was filled with love.

She was not always welcomed by her audiences. Once she stepped onto a stage and was met with loud hissing to which she boldly responded: “You may hiss as much as you please, but women will get their rights anyway. You can’t stop us, neither.” She then launched into the biblical story of Esther arguing that just as women in scripture, women today are fighting for their rights.

In May 1851, she was invited to speak at the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio where she delivered her most famous extemporaneous speech on women’s rights, later titled “And Ain’t I a Woman.” Her speech demanded equal rights for all women as well as for all African-Americans. Different versions of her speech have been recorded, but the standard text is what follows.

Well, children, where there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that ‘twixt the negroes of the South and the women at the North, all talking about rights, the white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what’s all this here talking about?

That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man–when I could get it–and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman?

Then they talk about this thing in the head; what’s this they call it? [member of audience whispers, “intellect”] That’s it, honey. What’s that got to do with women’s rights or negroes’ rights? If my cup won’t hold but a pint, and yours holds a quart, wouldn’t you be mean not to let me have my little half measure full?

Then that little man in black there, he says women can’t have as much rights as men, ’cause Christ wasn’t a woman! Where did your Christ come from? Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him.

If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again! And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them.

Obliged to you for hearing me, and now old Sojourner ain’t got nothing more to say.

After an extraordinary life, Sojourner Truth died at her Battle Creek, Michigan home on November 26, 1883. Her funeral was the largest that town had ever seen. Today we can answer unequivocally her question: “Ain’t I a Women?” Yes, yes indeed.

Related Posts

February 23, 2023

Missio plans partnership with Kairos University

Missio is excited to announce a new…

June 5, 2022

June 16, 27, and 30: Virtual Open House Orientations

You are invited to virtual open houses…

February 23, 2022

A Heartfelt Discussion with Sister Thelma White and Pastor Kevin Haynesworth

A Heartfelt Discussion with Sister…

July 16, 2021

Class of 1972 Virtual Reunion: Celebrating The First Graduating Class

As a part of our 50th anniversary…

April 15, 2021

May 13 Webinar: Participating with Our Missional God

The purpose for this webinar is to…

July 9, 2020

Webinar Recording: African Americans and Asians Together

This recorded webinar explores how the…

June 25, 2020

July 9 Webinar: African Americans and Asians Together

This forum seeks to explore how the two…

June 11, 2020

Webinar Recording: Courageous Conversations on Race Relations

In this recorded webinar, Missio…

June 9, 2020

June 11 Town Hall: Courageous Conversations on Race Relations

On Thursday, June 11, 2020 from 7-8:30…

May 20, 2020

June 18: Faith & Leadership When Lives Are on the Line

On June 18, 7-8:30 PM Major Marcus…

May 9, 2020

Faith in the Marketplace 2020: Faith & Work During COVID-19

In this online Faith in the Marketplace…

August 13, 2019

What if the Church Continued On With Business as Usual?

It is Sunday, July 21st, 2019 and the…

July 18, 2019

In Defense of Missional Theology: A Response to Mark Galli

Mark Galli, editor-in-chief of…

April 24, 2019

Faith in the Marketplace 2019: Living Missionally in the Everyday

Michael Gonzalez, Gino Curcuruto and…

March 12, 2019

April 9 Event: Bible/Theology Programs Open House

You are invited to the Missio Seminary…

February 11, 2019

February 28 Event: Connection & Conversation Night

Join Dr. Todd Mangum, fellow alums,…

January 21, 2019

A Walk through African American History and Culture

Professor Todd Mangum and Dr. Larry…

October 24, 2018

Eugene Peterson: The Man Who Translated – and Lived – The Message

My wife called me Monday afternoon with…

August 28, 2018

October 6 Event: Founders’ Day Celebration & Open House

As BTS embarks on a new journey into…

August 13, 2018

20 Questions That Shaped World Christian History

A man living on a small but significant…

August 12, 2018

Should You Get A Doctorate in Counseling or Psychology?

In recent weeks, I have had several…

October 23, 2017

Considering Systemic Abuse: Impact and Response

At the 2015 Community of Practice put…

October 22, 2017

Regarding Jerry Sandusky, Institutions, and Hating the Right Thing

Jerry Sandusky: football hero. Jerry…